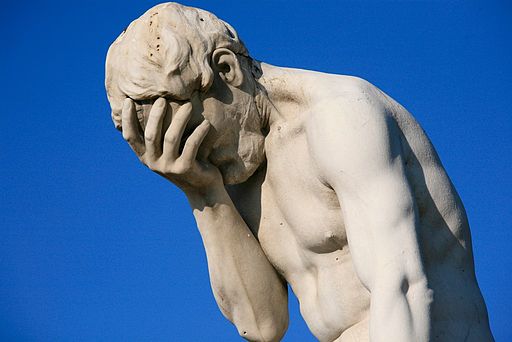

Facing cognitive dissonance

A few weeks ago, @MiraScriptura posted an article entitled “Bernard Lamborelle vs Mirror-Reading.”

Given I had briefly engaged with the author, I was looking forward to this article. I knew it would be different from everything else I had read on Abraham. I also knew it would be written respectfully.

The article was presented as a “compare and contrast between two different approaches regarding Abraham and Yahweh.” According to the author, “Mirror-reading is the process of mirroring the text in order to recreate the opposing narrative that the Biblical author was responding to. So, for example, if the Biblical writer says to do ‘x’, then the opposing narrative may have been saying not to do ‘x’.”

A challenging experience

I read the article a first time and couldn’t wrap my head around it. I had not been exposed to mirror-reading before; and found myself trying to make sense of a version of the story of Abraham, which had been broken down into separate “books” according to what Tzemah Yoreh refers to as Supplementary Hypothesis. The basic idea, which evolved from the well known Documentary Hypothesis developed by Julius Wellhausen, is that a hypothetical and original “Book of E” would have been later augmented by the “Book of J” and then by “The Bridger” to produce the familiar text of Gn 12-25 we find today in the Bible.

With some elements of the story purported to have originated from one book, and other elements from another book, I had to mentally project how these three separate stories had evolved separately and merged into one. To be honest, I struggled with the article and found the whole argumentation quite confusing. I almost gave up, blaming my inability to understand on a poorly structured post… Until I saw a tweet from @ElishabenAbuya (a fan of Tanach & Rabbinical writings I respect), who commented saying he felt the article was nicely written and well thought out:

My ego immediately reacted and went: “Gosh, what’s wrong with me? How come I am not able to see this?”

It is only at that moment that I came to doubt and realize that perhaps I was experiencing cognitive dissonance. Everything seemed so foggy to me. My brain got so used to the classic story that it just couldn’t connect the dots. It was experiencing uneasiness in a way that prevented my brain from understanding the logic, as if it had completely lost its ability to follow the arguments. The whole post appeared to me as non sequitur.

I took it as a challenge and an exercise to overcome this weird feeling. I went back and read the article a second time, and then a third time… I also read all the referenced material (Book of E, Book of J and Bridger). I was eventually able to wrap my head around the whole thing and start seeing the logic behind this different worldview… and while I can’t say I fully subscribe to the method, I eventually came to appreciate its logic.

This exercise definitely brought me to better appreciate just how difficult it can be for scholars and anyone who’s used to reading and understanding the story in a particular way to rewire their brain in order to grasp the new perspective that I am exposing in The Covenant. In the end, it has little to do with intelligence or good will. It is just the way our brain works.

Mirror Reading

I am not sure there is much value in responding to the article point by point. Not that it isn’t an interesting piece, but rather because we operate from worldview.

We both agree that Gn 12-25, much like many other texts of the Bible, have been manipulated by redactors over time. We disagree, however, on which part and why @MiraScriptura adheres to Tzemah Yoreh’s worldview, which looks at these texts as the combination of multiple speculative sources, which leads him to assert that “The Abraham Cycle is primarily concerned with resolving issues between the Israelites and the descendants of Abimelech.” Meanwhile, I look at Gn 12-25 as a mostly coherent and holistic narrative which is primarily concerned with explaining how Abraham and his descendants ended up inheriting the land of Canaaan and how this secular gift led to the development of a unique covenantal theology.

While working on my book, I became ever more convinced that the Bible did evolve over a very long period of time, which saw widely varying contexts, and where scribes had different reasons for wanting to adapt the narrative to either fit a particular propaganda, theology or simply to clarify what they thought the text meant. I also believe that a good interpretation of the Abrahamic Cycle should bring us to better understand why the Abrahamic Cycle, among all other ancient texts, was preserved and enshrined at the very core of Judaism. And while I can appreciate how breaking down a complex text such as Gn 12-25 into several “books” (as proposed byTzemah Yoreh’s) can be an attractive approach, I believe it is also important to recon that this practice introduces a whole new layer of subjectivity.

I have always regarded the most powerful hypothesis as the one requiring the fewer changes to the text to explain the most of it. It is true that the story of Abraham is perceived as disjointed when Yahweh and Elohim are understood to be one and the same deity, and I can understand how one gains coherence by separating the story into separate religious texts. However, the Dissociative Exegesis method I have developed allow us to fully integrate the text into one coherent secular story. I would therefore like to believe that the interpretation that I am proposing in The Covenant is superior to that of mirror-reading, but this is not for me to say (I am clearly biased!), but for you to decide.

My critic of mirror-reading would therefore be the same one I would level at any other textual analysis method: The fact it solves a textual problem, doesn’t mean it can solve all problems. By conjecturing too much on the prior existence of these books, I feel there is a risk for one to get carried away and lose sight of the fact that the only text we really have at our disposal and that needs to be explained is Gn 12-25 rather than the Books of J, E and Bridger.

A few observations

There are nevertheless a few observations on which we agree and disagree, and I will share my thoughts for sake of completeness.

@MiraScriptura brings up a good point when stressing the idea that Abraham would have been truly insulted to see his wife Sarah impregnated by Hammurabi, and that such an action would have weakened the ruler’s authority. @MiraScriptura suggests that Hammurabi would have more likely offered Abraham one of his daughter as a concubine, as it was often the case when sealing alliances.

Meanwhile, he rejects my suggestion that Yahweh should always be associated with the anthropomorphic character in the text. He writes: “This ‘gradual amalgamation’ of the terms ‘Yahweh’ and ‘Elohim’ allows Bernard to switch out Elohim for Yahweh wherever it suits his needs based on later scribal error or bias.” Actually, I do not switch out Elohim for Yahweh “wherever it suits my needs” What I am proposing is to systematically associate the anthropomorphic figure with Yahweh, and the immaterial one with Elohim. The “switch” is therefore not left to anyone’s subjectivity, but follows an objective rule. I have recently demonstrated that the Dissociative Exegesis gives us a 93% confidence level that the usage of these names in their particular context is intentional and not accidental.

@MiraScriptura also rejects my association of Yahweh with a Mesopotamian king. He suggests, instead, that Yahweh should be understood as originating from Edom, rather than Babylon. In support for his position, he cites Toorn, which calls upon a few later biblical texts to suggest he must have originated from Edom. While this is entirely possible (and even expected that later priests and prophets would have sought to bring their God closer to them), the biblical reference I am using (in addition to many other clues) belongs to the prelude of the story of Abraham and is rather unambiguous:

Gn 10:10 And the beginning of his kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh, in the land of Shinar.

This verse clearly states that the beginning of Yahweh’s kingdom was Babylon, near Akkad in the land of Sumer – which is precisely where Hammurabi’s reign began. In textual criticism, we learn that the most difficult of two explanations is often (but not always) the most original one – lectio difficilior potior. In this case, one would need to explain why else someone would have felt the need to write down that Yahweh came from Babylon.

I believe there are other reasons why Yahweh might be perceived today as having originated from Edom. These reasons would be related to Ishmael’s descendants, whom were assigned the title “aluf”. If you are curious as to this meaning and why they could be related, you might want to read my other post entitled Sarah, Mother Goddess of Israel.

Finally, Tzemah Yoreh’ idea of a Bridger text to explain Gn 14 tells me more about his inability to deal with this chapter than anything else. It is clear that anyone approaching the Abrahamic narrative from the perspective of a divine covenant will be tempted to toss Gn 14 aside as it doesn’t fit with the rest of the narrative. However, I have shown in The Covenant that Gn 14 fits perfectly the minute one adopts the perspective of a secular covenant. In fact, this text is a pillar argument of the hypothesis I am proposing.

Conclusion

I am very grateful for the work of @MiraScriptura as it shows the wide range of perspective one can take on the text. More importantly, it brought me to experience cognitive dissonance first hand. The most surprising aspect is that I didn’t became aware that I had fallen for it until an external event brought me to pay attention. Had I not been alerted by the tweet of @ElishabenAbuya, I would have moved on and never even realized.

I am now certain that I must have ran into cognitive dissonance before, but without ever being aware of it. Once our brain gets wired in a certain way, it becomes extremely difficult to rewire. Our brain functions like the spinning wheel of a gyroscope and it takes substantial energy to overcome its biases. Cognitive dissonance acts in a very insidious way, which makes it almost undetectable from within.

It does take a lot more than a clear logic to bring someone to immerse himself or herself into a different perspective. It requires letting go of certitudes and be prepared to wipe the slate clean – two things that the ego hates to do. More importantly, it takes a commitment and a real desire to understand. And this, requires us to be in a safe space where trust, empathy and respect prevails.

There is obviously a lot of stuff that makes no sense out there. However, there is a difference between reviewing the facts and disagreeing with them, and not being able to comprehend the logic. Next time you read something that is reportedly properly argued, but you can’t make heads or tails from it, take the time to ask yourself “could I be experiencing cognitive dissonance?”

One thought on “Facing cognitive dissonance”